Aksu v. Turkiye

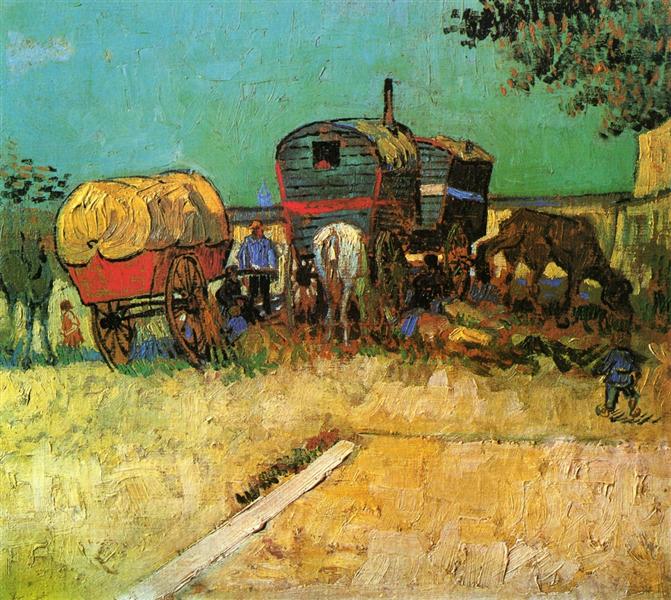

Vincent van Gogh, Encampment of Gypsies with Caravans (1888)

Ah, Turkiye, always managing to spice things up. In Aksu v. Turkiye, the Turkish government decided to play around with some stereotypes. But Mr. Aksu, a member of the Roma community, wasn’t laughing. You see, the government published a dictionary and a book that described the Roma as “miserly” and “thieves.” Yeah, not the kind of thing you put on a résumé, right?

Mr. Aksu wasn’t thrilled and headed straight to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), waving his Article 8 and Article 14 flags. He felt that Turkiye’s publications weren’t just a little offensive—they were a full-blown stereotype fest aimed at undermining his ethnic identity.

Stereotypes Gone Wild

Now, let’s talk about what these so-called “educational” materials included. The dictionary and book—yes, the ones funded by Turkiye’s Ministry of Culture—were full of fun little gems like calling Roma people “thieves” and “miserly.” According to the government, it was all in good educational spirit, meant to “inform” people about Roma culture. Sure, Turkiye, we’re buying it… not.

Aksu, though, wasn’t amused. He argued that this wasn’t information—it was negative stereotyping that chipped away at his sense of identity. But the Grand Chamber had its own thoughts.

What the Court Said: Freedom of Expression vs. Stereotyping

So, did the Court throw the book at Turkiye? Not exactly. In fact, the ECtHR didn’t find a violation of Aksu’s rights under Article 8 (right to private life). They said that, while the publications were a little rough around the edges, they were technically protected under freedom of expression (Article 10).

But wait, there’s a twist: the Court acknowledged that negative stereotyping could indeed impact ethnic identity and self-worth. So, they did see the harm but ultimately sided with the State’s freedom of speech. In other words, Turkiye’s publication won on a technicality—but it was still a slap on the wrist.

Freedom to Stereotype?

Here’s where it gets interesting. The ECtHR’s ruling essentially said: It’s not nice, but it’s not a violation. The Grand Chamber even suggested that Turkiye could have done better by labeling the stereotypes as “pejorative” or “insulting” instead of simply “metaphorical” (§ 85). You know, just a little extra touch of honesty would’ve been nice!

They also pointed out the importance of academic freedom in this case. According to the Court, it wasn’t Turkiye’s job to censor academic publications, even if they ruffled some feathers.

The Big Takeaway

So, what’s the moral of this legal drama? Negative stereotypes hurt, but they don’t always break the law—at least, not in this case. The Court saw the problem but chose to prioritize freedom of expression over Mr. Aksu’s hurt feelings. It’s a tough balance: how do we handle cultural stereotypes without trampling on the right to free speech?

And yet, by limiting someone’s freedom of expression, aren’t we also restricting the self-expression of a community? In the end, Aksu v. Turkiye is a win for Turkiye’s right to publish—though maybe next time they’ll think twice about the way they “inform” the public. And for the rest of us, it’s a reminder that stereotypes, even when protected by law, still leave a bad taste.